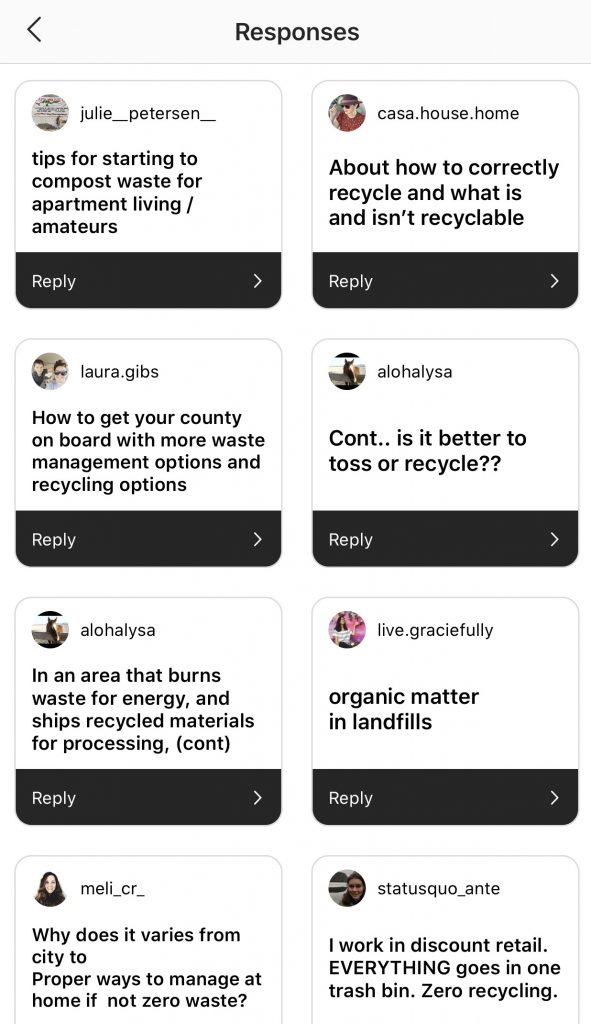

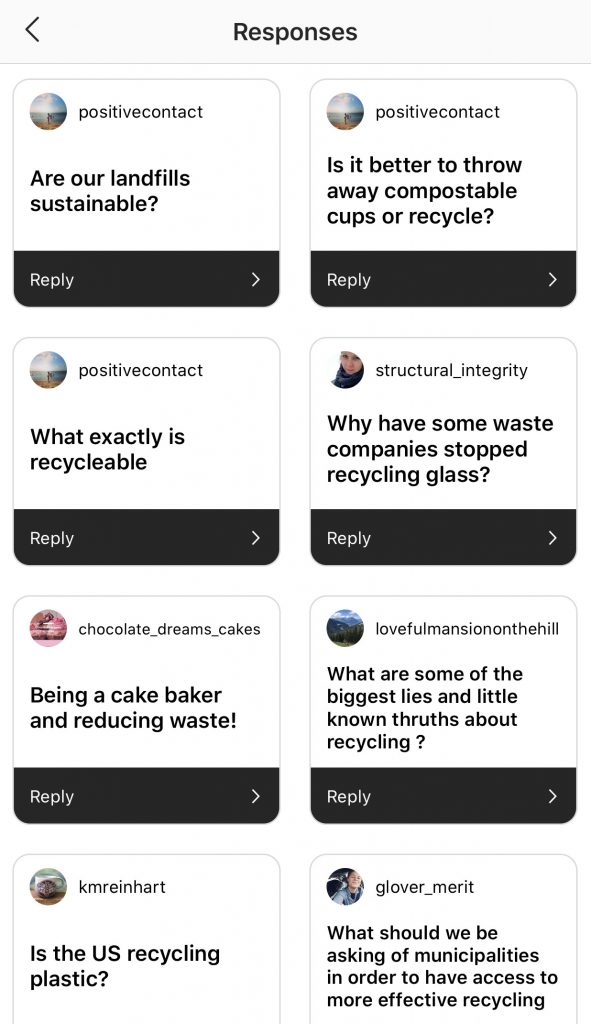

My mom recently asked her Instagram followers what kind of waste-related topics and questions they’d like to know more about from the perspective of a waste management student. She sent me screenshots of her responses and I noticed there were a lot of questions and criticisms about recycling. So I thought I would write a post about how recycling works and what we should all be doing to alleviate pressure on the system.

Q: How does recycling work?

A: Recycling is actually market based. Your municipality has a waste contractor collect recyclables on their behalf (some cities do their own residential waste collection, but cities will usually hire a contractor to do the work). The contractor eventually delivers the recyclables to a MRF (material recovery facility).

There, employees and a series of sorting equipment sort the material by type. The separated materials are compressed into large bales. These bales are sold to recycling companies. The revenue goes to the municipality, but recently, recycling has become an expense rather than a source of revenue. This is because the prices for recyclable commodities have plummeted since China stopped importing most postconsumer recycling. It’s a case of supply exceeding demand.

Q: Do recyclables actually get recycled?

A: Yes, some absolutely do. But others do not. It all depends on a variety of factors, including:

- Material type. Aluminum cans have a higher market value than other recyclable commodities, so it is easier to find buyers for them.

- The type of container used to put recyclables at the curb. Blue box contents can blow away during high winds.

- How it is sorted. Sometimes materials end up in the wrong bale, since sorting equipment isn’t perfect.

- Whether there is a buyer for the material. It is harder to find buyers for material with high processing costs and low market value, like plastic bags and polystyrene.

- Contamination. Workers at MRFs pull contaminated items off the sorting line and buyers reject bales that are too contaminated.

- Oil prices. Plastic is made from oil, so when oil prices are low, it is cheaper to make plastic from oil than it is to make it from recycled plastic. So manufacturers prefer not to use recycled plastic when virgin plastic costs less.

There’s a lot going on behind the scenes, including hard work by public servants to make sure that things get recycled. But there are also a lot of complicating factors, and sadly a lot of recyclable material does not get recycled. Often it doesn’t make it into the recycling bin in the first place, such as if it is littered or landfilled or blows away, but even if it does make it into the bin, it doesn’t always get recycled. When the market is flooded with recyclable material and municipalities can’t sell their own recyclable material, they often end up landfilling it when they run out of storage space (Rosengen et al., 2019).

Q: What is the China ban? Why was it implemented and what are the impacts?

A: In 2017, China heavily restricted imports of nonindustrial plastic waste (meaning postconsumer plastic waste—so the stuff you would throw in your recycling bin at home) (Wang et al, 2019). Prior to this, China was importing about half of the world’s postconsumer plastic waste (Wang et al, 2019). China restricted these imports because the materials that it was receiving were simply too contaminated. Contamination means that materials in a bale are dirty (food residue), or it means that a bale contains materials other than what the bale is supposed to be made of (so a cardboard bale containing plastics, for example). It’s hard to process contaminated materials because you’re adding confounding variables that can harm the process. If you’re processing paper into pulp and there are plastic bags added to that process, it’s going to create problems.

I think an important part of the China ban that gets overlooked are the impacts to paper recycling. We produce a massive amount of paper waste, and there aren’t enough buyers for it all. So bales of paper are getting landfilled now (Rosengen et al., 2019). Plastic has been getting more attention recently because of the horrific impacts to aquatic environments, but paper waste is a huge problem as well. Paper is organic material, so it produces methane when it decomposes in landfills. It’s not just the food waste creating methane—it’s all that paper waste as well. So minimizing plastics consumption is great, but if you’re just replacing plastic with paper-packaged products, that creates a different set of environmental problems.

The issue is not just plastics, but waste in general. We generate too much waste and our waste management systems and the environment are overwhelmed by it all.

Q: What’s the deal with contamination? Why is recycling in Canada and the United States so contaminated?

A: A lot of people simply don’t recycle properly. So they’ll put peanut butter jars with peanut butter still in them in the recycling, or they’ll put materials in their recycling bins that aren’t accepted by whoever collects the materials in that bin.

For example, a lot of cities have stopped accepting plastic bags. The City of Mountain View, California where my mom lives is an example—plastic bags are not accepted for recycling there. I live in the City of Kawartha Lakes, Ontario, and plastic bags are accepted here. It’s easy to understand why people get so confused about recycling—the rules differ from city to city. There are no provincial, statewide, or national standards for recycling acceptance criteria. These standards are in the works in Ontario, but whether they materialize will depend on whether the provincial government decides to go ahead with them.

Contamination isn’t always the fault of the consumer—a person could do everything right and have a clean recycling bin free of contamination, but those materials could get dumped into a garbage truck filled with dirty items that end up contaminating some of what would have otherwise been recyclable. It can also happen when the sorting equipment at a MRF makes errors—sorting equipment can accidentally put plastic into a bale of cardboard, for example.

Q: Are compostable plastics recyclable?

A: No. Please don’t put compostable plastics in the recycling! They usually belong in the trash, since a lot of municipal green bin programs don’t accept them. (Green bin programs are a whole other topic that I’ll get into in another post).

Compostable plastics ending up in the recycling is getting to be a big problem. Even though they often have a triangle on the bottom, you aren’t supposed to recycle them. Compostable plastics don’t have the same chemical composition as regular petroleum-based plastics. They don’t have the same additives and they melt at a lower temperature. So when they get mixed into bales of regular petroleum-based plastic this can cause problems down the line. Buyers will either reject the material due to the contamination present or they will purchase it and attempt to process it but then landfill the material once the contamination presents issues during the recycling process.

Personally I don’t think compostable plastics are the way to go—a lot of green bin programs don’t accept them, so they don’t alleviate the pressure on landfills and incinerators. And when they’re put in the recycling, they can wreak havoc on the process. Besides the issues that compostable plastics create for waste management systems, I think that compostable plastics really just enforce the disposability mindset that we need to try to move away from.

Even if these materials do make it into a green bin program that can properly process them, manufacturing them uses resources and creates emissions. So it’s better to use something reusable, because then you extract the resources to manufacture it one time, instead of extracting and discarding resources multiple times.

Q: What’s the deal with glass?

A: This is a tough one. In the United States, only about a third of glass gets recycled (Jacoby, 2019). One reason more doesn’t get recycled is because glass breaks. When you hear that crash when a container of recyclables is dumped into the garbage truck—that’s the sound of glass breaking. And because glass is commingled with other materials in most American and Canadian collection programs, recycling rates are low due to contamination.

Broken glass gets contaminated with other materials. So it’s difficult to recycle because it’s not pure feedstock. Sometimes this broken glass is sold to be used for sandblasting or to be used as aggregate. It’s hard to turn it back into glass unless it is pure glass—so glass bottles and jars that aren’t contaminated.

The Beer Store in Canada has an excellent model for recycling glass—and it even washes and reuses brown beer bottles. They key to success here is that glass is collected separately and it is not mixed with other materials like plastics, metal and paper products. In European countries, glass is also collected separately from other recyclable materials, making the glass recycling rate in Europe a whopping 90% (Jacoby, 2019). But in Canada and the United States, there’s a significant chance that the glass you put in your recycling bin will break and end up as aggregate or sandblasting material.

Q: Is _____ recyclable?

A: I actually can’t fully answer this question—it totally depends on your municipality. Your municipality should have a list of what they accept for recycling, or a recycling guide. They may also have a waste & recycling calendar, or they might even have a what goes where searchable database. Type “waste and recycling –your city’s name–” into google and see what you can find. If you call them, they would more than likely be happy to help!

There are other times when this gets trickier. Institutions and businesses (malls, schools, multiresidential buildings, restaurants, etc.) often have their own waste contractors with different acceptance criteria than the cities that they’re located in.

For example, I used to live in a six-story student condo in the City of Guelph, Ontario. Curbside collection in Guelph is managed by the city of Guelph. But the building I lived in had hired WasteCo to collect its waste. So the acceptance criteria at my condo was different than the City of Guelph’s acceptance criteria for their curbside waste collection program. Pretty confusing! This goes back to the idea that we should have provincial, statewide, or national standards for what is accepted for recycling.

Q: What is wishcycling?

A: Wishcycling is when people put things into their recycling bin in the hopes that that thing will be recycled. They aren’t actually sure if that thing is accepted for recycling or if it will get recycling, but they decide to give it a try.

Unfortunately, this creates more problems than if the person had just thrown that item in the trash. Wishcycling introduces contamination into the recycling stream, which is a huge problem that waste management systems have to grapple with. So even if it makes you feel uncomfortable or guilty, if you really aren’t sure where something goes, throw it in the garbage. Better yet, if you’re in the store and you want to buy something, but the packaging looks like it will be confusing to dispose of, avoid buying it if you can.

Q: Should people give up on recycling?

A: The thing to understand about recycling is that the system is totally overwhelmed. It has also been heavily promoted by packaging and beverage manufacturers as a way for them to wash their hands of any responsibility for the products that they create.

Recycling exists for a reason, but ideally it needs to exist as part of a circular economy. Right now we have a linear economy where we extract, manufacture and dispose of resources. As a whole our society doesn’t really think about reusing things, repairing things or reducing consumption (although these concepts have been growing in popularity in recent years). We produce too much waste and recycling is an imperfect, end of pipe solution.

When you generate waste, if you know for sure that it is accepted for recycling in your location, you should recycle it instead of putting it in the garbage. But what we really all need to do is get to the point where we’re minimizing the volume of waste that we produce. Right now we are producing a massive amount of packaging waste and there simply aren’t enough buyers for all of this material that we’re generating. So we need to stop and think about what we are buying.

For some people, this is really hard. Maybe they are living in poverty, working two jobs and struggling to pay for food. But what about those of us who are fortunate enough to have a good standard of living? Surely we can do something, right? It is hard to be perfect, but most people can make a dent. Even if you start with something small. You don’t have to be a person who fits all their waste into a jar. Don’t feel intimidated by photos of beautiful zero-waste lifestyles on Instagram either.

I think it’s important to remember that just because you can’t do everything doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try. If everybody reduced their waste by 25% or 50%, that would have huge environmental benefits. So don’t feel discouraged because you can’t do it all, just remember that you can do something.

References

Jacoby, M. (2019, February 11). Why glass recycling in the US is broken. Chemical & Engineering News.

Rosengen, C., Witynski, M., Li, R., Crunden, E. A., Boteler, C., & Pyzyk., K. (2019, November 15). How recycling has changed in all 50 states. Wastedive.

Wang, C., Zhao, L., Lim, M. K., Chen, W. Q., & Sutherland, J. W. (2020). Structure of the global plastic waste trade network and the impact of China’s import Ban. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 153, 104591.

Mary Katherine Glen graduated from the University of Guelph with a degree in Environmental Governance and now attends Fleming College for a post-graduate certificate program in waste management.

great article!

This was extremely informative and helpful. Thank you!

Great post and good reminder that a 25 or 50% reduction would still be a massive improvement. I still fall into the guilt trap of feeling I am never doing it well enough even though I try very, very hard! Guilt is not useful and a bit depressing in the long run.

Madeleine

Great job explaining the problem, Mary Katherine. You clearly have a great talent, like your mother, researching your subject and explaining in digestible terms for the general public. Thank you, both for your diligent and ongoing work!

Thank you for explaining these things in a easy to understand way!

This is a really good article, thanks Mary. One of the most important things that people forget about the three “Rs” Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle, is that recycle is the LAST on the list. We have to all be more creative about reducing these materials first, and reusing what we can. Then, the last resort is recycling.

Recycling can be intimidating at first and this is great info! Thanks for sharing!

Really learned a lot on this complicated issue. Appreciate the many recycle tips, expertise and practical advice. Thank you!